- Research

- Open access

- Published:

A scoping review of outdoor food marketing: exposure, power and impacts on eating behaviour and health

BMC Public Health volume 22, Article number: 1431 (2022)

Abstract

Background

There is convincing evidence that unhealthy food marketing is extensive on television and in digital media, uses powerful persuasive techniques, and impacts dietary choices and consumption, particularly in children. It is less clear whether this is also the case for outdoor food marketing. This review (i) identifies common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, (ii) summarises research methodologies used, (iii) identifies available evidence on the exposure, power (i.e. persuasive creative strategies within marketing) and impact of outdoor food marketing on behaviour and health and (iv) identifies knowledge gaps and directions for future research.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted of Medline (Ovid), Scopus, Science Direct, Proquest, PsycINFO, CINAHL, PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and a number of grey literature sources. Titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher. Relevant full texts were independently checked by two researchers against eligibility criteria.

Results

Fifty-three studies were conducted across twenty-one countries. The majority of studies (n = 39) were conducted in high-income countries. All measured the extent of exposure to outdoor food marketing, twelve also assessed power and three measured impact on behavioural or health outcomes. Criteria used to define outdoor food marketing and methodologies adopted were highly variable across studies. Almost a quarter of advertisements across all studies were for food (mean of 22.1%) and the majority of advertised foods were unhealthy (mean of 63%). The evidence on differences in exposure by SES is heterogenous, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions, however the research suggests that ethnic minority groups have a higher likelihood of exposure to food marketing outdoors. The most frequent persuasive creative strategies were premium offers and use of characters. There was limited evidence on the relationship between exposure to outdoor food marketing and eating behaviour or health outcomes.

Conclusions

This review highlights the extent of unhealthy outdoor food marketing globally and the powerful methods used within this marketing. There is a need for consistency in defining and measuring outdoor food marketing to enable comparison across time and place. Future research should attempt to measure direct impacts on behaviour and health.

Background

Advertising of foods and non-alcoholic beverages, (hereafter food advertising), particularly for items high in fat, salt and/or sugar (HFSS), has been identified as a factor contributing to obesity and associated non-communicable diseases globally [1]. People from more deprived backgrounds or ethnic minority groups are disproportionately targeted and exposed to greater food marketing across a range of platforms [2], and this may contribute to social gradients in obesity and associated health inequalities [3]. Marketing is defined by the American Marketing Association (AMA) as “the activity, set of institutions, and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large” [4], and advertising is a key aspect of marketing, which seeks to “inform and/or persuade members of a particular target market or audience regarding their products, services, organizations or ideas” [5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) assert that the impact that food marketing has on consumer behaviour is dependent on both ‘exposure’ and ‘power’ [6]. Exposure is the frequency and reach of the marketing messages and power is the creative content and strategies used, both of which determine the effectiveness of marketing [6]. Hierarchy of effects models of food marketing consider that the pathways for these effects are likely to be complex [7], with evidence demonstrating that food marketing impacts food purchasing [8], purchase requests [9], consumption [10, 11] and obesity prevalence [12].

Evidence suggests that children are likely to be more vulnerable to marketing messages than adults [13,14,15]. Furthermore, it has been proposed that the scepticism towards advertising that is developed in adolescence does not equate to protection against its effects [16], leaving both young children and older adolescents vulnerable to the effects of food marketing [17]. For this reason, policies enacted generally aim to decrease the exposure or power of food marketing to children, and so this is where much of the research is focused. Despite this, it is apparent that adults are similarly affected by food marketing [18], and therefore also likely to benefit from restrictions [19].

In 2010, WHO called on countries to limit the marketing of unhealthy foods, specifically to children [6]. Various policies have since attempted to enforce restrictions on HFSS advertisements [20], however, restrictions outdoors remain scarce [21] and implementation and observation of such restrictions has been found to be inconsistent and problematic [22].

Previous reviews have collated the evidence on the exposure, power and impact of food advertising on television [23,24,25], advergames [26, 27], sports sponsorship [28, 29] and food packaging [30, 31] and in some cases across a range of mediums [2, 32]. An existing scoping review [33] documents the policies in place globally to target outdoor food marketing, and the facilitators and barriers involved in implementing these policies. The lack of effective policies for outdoor food marketing may reflect the comparatively little evidence or synthesis of evidence on outdoor marketing or its potential role in contributing to overweight and obesity, relative to that for other media. Additionally, there are challenges in measuring outdoor marketing exposure compared to television and online [34]. As countries such as the UK and Chile [35] move to strengthen restrictions on unhealthy food marketing via television, digital media and packaging, it is plausible that advertisements will be displaced to other media such as outdoor mediums so that brands can maintain or increase their exposure [36, 37].

Despite being a longstanding and widely used format [38] there is no agreed definition for outdoor food marketing. This may have implications for the comparability of data across study designs, which has been reported as a limitation in previous reviews [11, 39]. Identifying the common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, alongside considering best practice methodologies for outdoor marketing monitoring and impact research, are important steps to support the generation of robust, comparable evidence to underpin public health policy development.

Given that 98% of people are exposed to outdoor marketing daily [40], it is an efficient form of marketing for brands [41], and is likely successful in influencing purchase decisions through targeting potential shoppers in places the brands are sold [42]. Food marketing through media such as television and advergames have been shown to impact eating and related behaviours such as purchasing [43,44,45,46], and the evidence on this marketing and body weight has satisfied the Bradford Hill Criteria [47], which is used to recognise a causal relationship between two variables. However, the impact that outdoor marketing has on eating related outcomes is less clear.

Therefore, this scoping review aims to (i) identify common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, (ii) summarise research methodologies used, (iii) identify available evidence on the exposure, power (i.e. persuasive creative strategies within marketing) and impact of outdoor food marketing on behaviour and health with consideration of any observed differences by equity characteristics such as socioeconomic position and (iv) identify knowledge gaps and directions for future research.

Methods

Approach

Given the broad objectives, a scoping review [48] was conducted and reported in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [49] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [50]. The review was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/wezug).

Search strategy

A detailed search strategy was created by the research team (see supplementary material 1), which included an experienced information specialist (M.Ma), to capture both published and unpublished studies and grey literature. Search terms related to food, outdoor and marketing were developed based on titles and abstracts of key studies (identified from preliminary scoping searches) and index terms used to describe articles. For grey literature sources simple terms “outdoor food marketing” and “outdoor food advertising” were used. Searches were conducted between 21st January and 10th February 2021.

Databases searched for academic literature included Medline (Ovid), Scopus, Science Direct, Proquest, PsycINFO, CINAHL, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. An additional supplementary PubMed search was conducted to ensure journals and manuscripts in PubMed Central and the NCBI bookshelf were captured. Grey literature searches were conducted of databases Open Access Theses and Dissertations, OpenGrey, UK Health Forum, WHO and Public Health England. Other searches for grey literature included government websites (GOV.uk), regulatory and industry body websites (World Advertising Research Centre Database, Advertising Standards Authority) and NGO sites (Obesity Health Alliance, Sustain).

Eligibility criteria

Primary quantitative studies assessing marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverage brands or products encountered outdoors in terms of exposure, power or impact were considered for inclusion. We defined both marketing and advertising as per the AMA definitions [4, 5].

Examples of outdoor marketing included billboards, posters, street furniture and public transport. Exposure was defined as the volume of advertising identified, with consideration of the brands and products promoted. Power of outdoor marketing was defined as the strategies used to promote products (e.g. promotions, characters) [51]. Eligible behavioural impacts of outdoor marketing were food preference, choice, purchase, intended purchase, purchase requests and consumption. Health-related impacts were body weight and prevalence of obesity or non-communicable diseases. Non-behavioural outcomes were ineligible, e.g., brand recall, awareness, or attitudes.

Studies in which outdoor marketing could not be clearly isolated from other marketing forms [46], or food could not be isolated from other marketed products (e.g. alcohol and tobacco) were excluded. Studies of health promotion (e.g., public health campaigns) were ineligible. Qualitative studies and reviews were not eligible for inclusion; however, reference lists of relevant reviews were searched.

Selection of sources of evidence

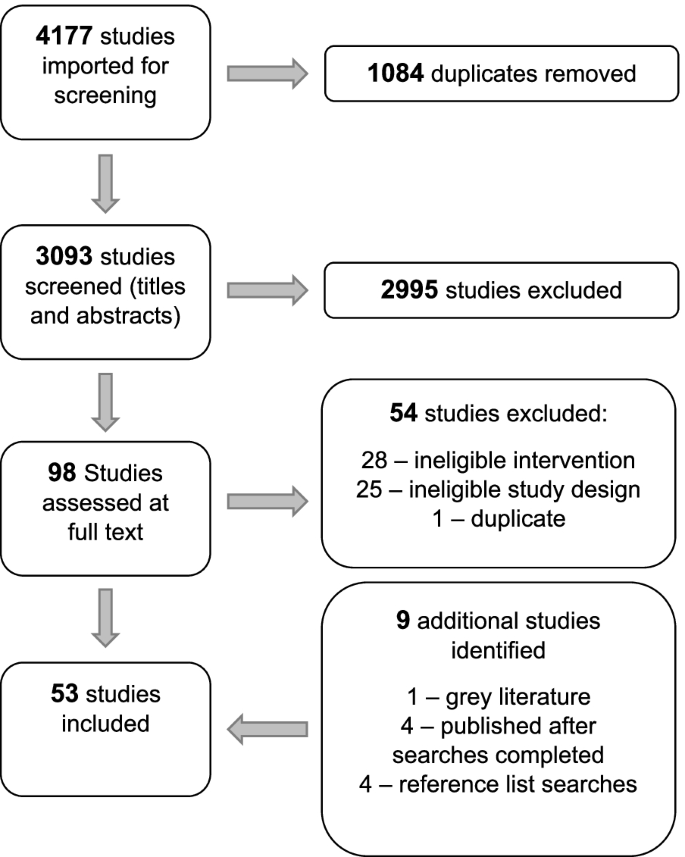

The full screening process is shown as a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). Titles and abstracts were screened by one researcher (AF). Full text review was conducted independently by two researchers from a pool of four (AF, M. Mu, RE & HM). Disagreement was resolved by discussion and where necessary (n = 4 articles) a third reviewer (EB) was consulted. Covidence systematic review software was used to organise the screening of studies. Inter-rater reliability for the full-text screening was high, with estimated agreement of 95.7% and a Kappa score of 0.91.

Data charting

The extraction template was developed and piloted prior to data extraction. For more detail on the information extracted from each article see supplementary material 2. Discrepancies in extraction were resolved by discussion. As the aim was to characterise and map existing literature and not systematically review its quality, as is common in scoping reviews [52] quality assessment (e.g. risk of bias) was not undertaken.

Synthesis of results

Studies that defined outdoor food marketing were grouped to identify common criteria used in definitions. Methodologies used to measure exposure, power and impact are summarised. Studies were grouped into exposure, power and impact for synthesis, with relevant sub-categories to document findings related to equity characteristics. We deemed foods classed as “non-core”, “discretionary”, “unhealthy”, “less healthy”, “junk”, “HFSS”, “processed”, “ultra-processed”, “occasional”, “do not sell”, “poorest choice for health”, “less healthful”, “ineligible to be advertised”, and “not permitted” as unhealthy.

Results

Study selection

After removal of duplicates from an initial 4177 records, 3093 records were screened. Ninety-eight articles were then full-text reviewed. Fifty-four studies were excluded here (supplementary material 3). After grey literature and citation searches, the final number of included studies was 53.

Characteristics of included studies

All studies (n = 53) measured exposure to outdoor food marketing, n = 12 also measured power of outdoor food marketing, and n = 3 measured impact. N = 15 studies provided at least one criterion through which outdoor food marketing was defined, beyond stating the media explored.

Studies were conducted across twenty-one countries, the majority took place in the USA (n = 16) [53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], and other high-income countries (n = 23) as categorised by the world bank [69] (Tables 1, 2 and 3).

Of studies including participants (n = 7), three measured exposure of children between the ages of 10 and 14 [89, 93, 102], two surveyed caregivers of children aged 3–5 [70] (79.2% mothers) and 0–2 years [85] (100% mothers) and two studies collected data from adults in select census tracts [53, 71].

What common criteria are used to define outdoor food marketing?

As shown in Tables 1, 2 and 3, the majority of studies (n = 33) encompassed a combination of outdoor media [53,54,55, 58, 60,61,62, 65,66,67,68, 72, 73, 75, 76, 78,79,80, 80,81,82,83,84, 87,88,89, 91, 92, 94, 97, 98, 102,103,104]. Many (n = 11) focused on advertising solely on public transport property [64, 70, 71, 86, 90, 93, 95, 99,100,101, 106], five studies focused exclusively on billboards [63, 74, 77, 85, 96] and four measured advertising outside stores or food outlets [56, 57, 59, 105].

Outdoor food marketing was inconsistently defined across studies. All studies stated the media they were measuring and some defined marketing or advertising generally, but often not how it related to the outdoor environment. Studies that provided specific criteria for outdoor food marketing (n = 15) or an equivalent term (i.e. outdoor food advertising) beyond simply stating the media recorded are listed in Table 4. Figure 2 represents the criteria referred to most frequently when defining outdoor food marketing.

What methods are used to document outdoor food marketing exposure, power, and impact?

Most included studies (n = 49) were cross-sectional, although four were longitudinal [68, 90, 95, 100]. The methods used to classify foods were inconsistent, for example, often local nutrient profiling models were used to classify advertised products as healthy or not healthy (e.g. [80]), however in some cases the number of advertisements for specific food groups were tallied (e.g. [56]). Forty-two studies assessed the frequency of food advertising through researcher visits to locations. In four [82, 83, 86, 93] studies, researchers visited streets virtually, through Google Street view. Real, rather than potential exposure was measured in three studies [89, 93, 102]. In two cases, children wore cameras which documented advertisements encountered in their typical day [89, 102], and in a final study, children wore a global positioning system (GPS) device so researchers could track when they encountered previously identified advertisements [93]. Self-reported retrospective exposure (frequency of encountering outdoor food advertising) was measured in three studies [70, 71, 85].

When measuring advertising around schools/places children gather, researchers typically created buffer zones, ranging from 100 m [81] to 2 km [105], with 500 m being the most frequent buffer size (n = 8) [77, 78, 86,87,88, 95, 97, 104]. Four studies used multiple buffers [82, 87, 93, 97], allowing for comparison between the area directly surrounding a school (e.g. < 250 m) with an area further away (e.g. 250-500 m) [87], one study compared advertising in Mass Transit Railway stations in school and non-school zones [90], and another used GPS point patterns to determine the extent of advertising around schools [92].

Content analysis was used to characterise the food types promoted and strategies used in the advertising. Two studies investigated price promotions [55, 56], two identified promotional characters and premium offers [75, 78], one specifically assessed child-directed marketing [57]. Others examined a mix of strategies including sports or health references, cultural relevance and emotional, value or taste appeals [54, 73, 74, 76, 79].

All three studies measuring the impact of outdoor food advertising used self-reported data. In a study conducted in Indonesia [70], caregivers reported the frequency of food advertising exposures in the past week, and their children’s frequency of intake of various confectionaries at home in the last week. In a study conducted in the US [53], individuals reported consumption of 12 oz. sodas in the last 24 hours, and odds of exposure was assessed by the extent of advertising in surrounding areas. In the UK study [71], participants reported exposure to HFSS advertising in the past week, and body mass index was calculated from participants’ reported height and weight.

What is known about exposure to outdoor food marketing?

Content of food marketing

Fifty-three studies investigated outdoor marketing exposure (Tables 1, 2 and 3), n = 22 reported specifically on exposure around schools or places children gather, n = 9 documented exposure on public transport and n = 4 outside stores/establishments. The remaining n = 21 measured exposure across multiple settings.

Food products were promoted in between 7.8% [64] and 57% [91] of advertisements, the mean across studies was 22.1%. Of food advertisements, a majority (~ 63%: range 39.3% [64] - 89.2% [89]) were categorised as unhealthy. Healthier foods were advertised far less, with studies generally reporting between 1.8% [97] and 18.8% [91] of food advertisements being for healthier products. Fast food (n = 17) and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs; n = 22) were frequently n amed as some of the most advertised product types.

Coca Cola was frequently stated as the most prominent brand advertised [73, 75, 88, 91, 100]. Around 5% of all outdoor food advertisements in New Zealand [78] and Australia [100] were promoting a brand (rather than a specific product), however there were no brand only advertisements identified in a UK study [80].

Marketing to children

Over half of the studies included (n = 29) sought to examine children’s exposure to food advertising. One UK study [93] concluded that while it was unlikely that unhealthy products were advertised on bus shelters surrounding schools (100-800 m), children, particularly in urban areas, were likely to encounter advertising on their journeys to and from school. All other studies found food advertising to be prevalent around schools, often promoting unhealthy products, although in three studies, a minority of schools (20.4% [78], 15.4% [79], 33.3% [103]) did not have any food advertising nearby. Four studies found that there was more food advertising closer to schools or facilities used by children and adolescents, compared to areas further away from these facilities [87, 97], specifically for unhealthy or processed foods [87, 90] and snack foods [82], however one study found SSB advertisements increased as distance from schools increased [92].

Differences by socioeconomic position/ethnicity

Eight studies considered differences in exposure by ethnicity. Three of these found that ethnic minority groups were exposed to more food advertising [55, 58, 62], for example, schools in the US with a majority Hispanic population were found to have more total advertisements and establishment advertisements in surrounding areas [55], whilst in New York City, for every 10% increase in proportion of Black residents there was a 6% increase in food images and 18% increase in non-alcoholic beverage images [58]. In addition to this, associations were found between sugary drink advertisement density and Percentage of Asian or Pacific Islander residents and percentage of Black, non-Latino residents [62]. Two studies found that multicultural neighbourhoods had a higher proportion of food advertisements [94] and higher density of unhealthy beverage advertisements [61]. Unhealthy food [63] and beverage [61] advertising were found to be more prevalent in ethnic minority communities. Low-income communities with majority Black or Latino residents had greater odds of having any food advertising [53], generally more food and beverage advertising and greater unhealthy food space [61] compared to white counterparts. A US study [56] found that differences in exposure to food and beverage, and soda advertisements by ethnicity were no longer significant after controlling for household income.

Twenty-six studies considered differences in exposure by SES, five of these did not find a relationship [60, 71, 83, 93, 99]. Two studies showed that food and beverage advertisements were more prevalent in low SES communities [56, 94]. Schools characterised by low SES had a higher proportion unhealthy food advertising nearby in two studies [78, 104], although in one instance there was no significant difference in the number of unhealthy food advertisements [78]. One study conducted in Sweden [84] found no significant difference in the proportion of food advertisements by SES, however there was a significantly greater proportion of advertisements promoting ultra-processed foods in the more deprived region.

Foods more frequently advertised in low SES areas were: SSBs, hamburgers and kebabs, diet soft drinks, vegetable snacks, dairy with no added sugar [103], staple foods [91], flavoured milk and fruit juice [101]. Low income communities in the US had lower odds of fruit and vegetable advertisements at limited service stores [56] and a higher density of unhealthy beverages [61, 62] compared with higher-income communities.

Two studies found no significant difference in the number of core advertisements by SES [98, 100], however a study of outdoor food advertising in Uganda found that there were more healthy food advertisements in high income areas [75]. Advertisements for fast food, takeaways, hot beverages and soft drinks were found to be more frequent in high-income areas [91, 96, 101].

A study comparing four schools of varying deprivation found the school with lowest deprivation had no advertisements but there was no clear trend in extent of advertising by deprivation [105]. Two studies conducted in Mexico [81] and New Zealand [86] found outdoor food advertising to be more frequent around public schools than private schools, however a study in Uganda [75] found no significant difference in the number of core foods advertised around private and government funded schools, in all three studies private school was considered a proxy of high SES. In this New Zealand study, low decile areas had the greatest number of advertisements for non-core food, core food and non-core food and beverage, however when high decile schools were combined with areas around private schools, the greatest number of all food and beverage advertisements and non-core advertisements were found in high SES areas [86].

What is known about the power of outdoor food marketing?

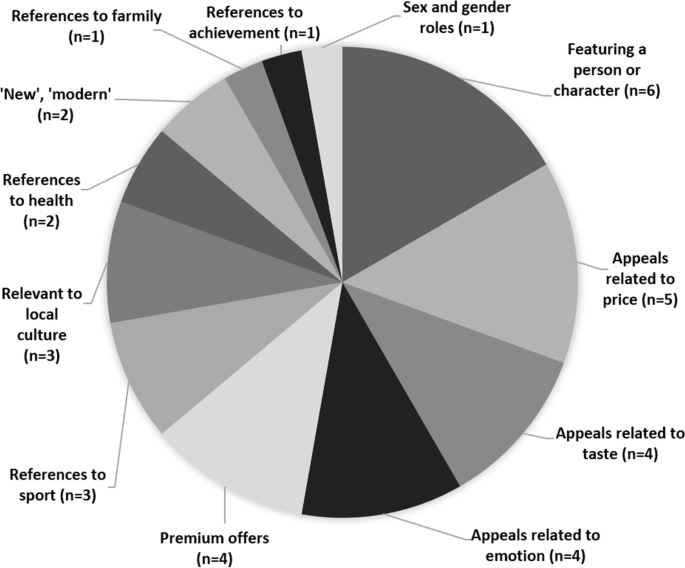

Twelve studies documented the power of outdoor food marketing (Table 2). This was measured by quantifying the use of a range of persuasive creative strategies and child-directed marketing. The persuasive creative strategies observed across studies are shown in Fig. 3.

Observed power

There was evidence of variation in the use of persuasive creative strategies in outdoor advertising, with premium offers (e.g. buy one get one free [78]) utilised in between 7.84% [74] and 28.1% [78] of food advertisements, and the proportion of advertisements featuring a person or promotional character ranging from 2.8% [79] to 46.8% [73]. Other strategies frequently identified were appeals related to price [55, 56, 72, 74, 76], emotion [72, 74, 76, 77] and taste [72, 74, 76, 77].

The proportion of advertisements considered to be targeted just at children or young people ranged from less than 1% [58] to 10.4% [73]. Studies assessing appeals to children considered the use of cartoon characters, popular figures, child models or characters, colours or images, toys and the placement of the advertisement [58, 64, 73, 83].

Often, the foods promoted using persuasive creative strategies were soft drinks [73, 76], non-core foods [77] and fast foods [57, 76], however one study [75] observed outdoor food advertising in Uganda and found that 15% of healthy food advertisements used promotional characters.

Differences by socioeconomic status/ethnicity

A US study [55] found that schools with a majority Hispanic population (vs. low Hispanic population) had significantly more advertisements featuring price promotions within half a mile of the school. Price promotions were also more frequent outside supermarkets in non-Hispanic Black communities in the US [56], although this was no longer significant after controlling for household income. Supermarkets in low-income communities were significantly more likely to have price promotions [56] and being located in middle-income (compared to high) and black communities was marginally associated with increased odds of child-directed marketing [57]. Sometimes, local culture was referenced in food advertising through persuasive creative strategies [54, 76, 77], for example a US study quantifying advertisements in a Chinese-American Neighbourhood [54] found food advertisements were frequently relevant to Chinese culture (58.9% of food and 59.04% of non-alcoholic beverage advertisements), often featuring Asian models.

What is known about the impact of outdoor food marketing?

Three studies (Table 1) [53, 70, 71] explored associations between exposure to outdoor food advertising and behavioural or health outcomes, two of these found a significant positive relationship. Lesser et al. (2013) [53] found that for every 10% increase in outdoor food advertisements present, residents consumed on average 6% more soda, and had 5% higher odds of living with obesity. In Indonesia [70] self-reported exposure to food advertising on public transport was associated with consumption of two specific HFSS products. No associations were found between exposure and consumption of the other eight products considered. A UK study [71] found no significant association between self-reported exposure to HFSS advertising across transport networks and weight status. No studies measured differences in impact in relation to equity characteristics.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review is the first to collate the criteria used to define outdoor food marketing, document the methods used to measure this form of marketing, and identify what is known about its exposure, power and impact.

Fifty-three studies were identified which met all eligibility criteria. In brief, of studies with a definition, the criteria referenced most were; on or outside stores/establishments; and stationary signs/objects. The methods used to research outdoor marketing include self-report data, virtual auditing, in-person auditing, and content analysis. There was little consistency in the approach used to classify foods as healthy or unhealthy, although nutrient profiling models were used in some studies.

Food accounted for an average of 22.1% of all advertisements, the majority of foods advertised were classed as unhealthy (63%). Ethnic minority groups were generally shown to have higher exposure to outdoor food advertising, but findings on differential exposure by SES were inconsistent.

Studies showed frequent use of premium offers, promotional characters, health claims, taste appeals and emotional appeals in outdoor food advertisements. There was limited evidence of relationships between exposure to food marketing and behavioural or health outcomes.

Common criteria used to define outdoor food marketing

Eight out of fifteen studies (Fig. 2) stated that outdoor food marketing must be on or outside of stores or establishments, seven studies included stationary signs or objects in their definition and five studies stated that advertisements must be visible from the street or sidewalk. However, the defining criteria was inconsistent across the fifteen studies, and some of the most referenced criteria are problematic. Although stationary signage is an important aspect of outdoor marketing, this excludes forms of marketing on transport e.g. the exterior of buses. Equally, not all outdoor marketing may be “visible from the street or sidewalk”, this could exclude advertising on public transport property, i.e. station platforms. Additionally, the share of digital out-of-home advertising rose from 14% in 2011 to 59% in 2020 [107]. Three studies did aim to document digital advertising [60, 63, 90] through observing a digital board for a set amount of time. This medium is likely to become more prevalent over time globally, and there are challenges due to its changing and interactive nature [108]. The literature appears dominated by studies of advertising. This may reflect that most marketing encountered outdoors is advertising, conversely, it may be that the literature is yet to consider some newer forms of marketing, such as increased digital platforms. It will be important for future research to consider the evolving nature of outdoor marketing and how this should be measured.

Only fifteen studies defined outdoor food marketing as a term. This has likely been a factor influencing the heterogeneity observed across studies (e.g. differences in scope), as inconsistencies in defining a factor can negatively impact the development of an evidence base [109]. Researchers should endeavour to work towards an agreed definition, perhaps through use of the Delphi method of consensus development [110], in order to improve consistency in the resulting research. However, this method can be open to bias if the researchers are of the same background as the experts involved [109] therefore it is important that any definition developed aligns with criteria used by industry to reduce likelihood of bias.

Methods used in outdoor food marketing research

Outdoor food marketing exposure and impact were measured using self-reported data, which may lack validity, as advertising can influence brand attitudes whether consciously or unconsciously processed [111]. While it can be useful to know the extent that individuals process advertising, this may not be a true representation of exposure. Equally, participants may alter their response to appear socially desirable which has previously resulted in misreporting of height and weight data [112].

Using Google Street View as an auditing tool is beneficial in saving time and resources whilst gathering large samples [113], however almost one third of advertisements in one study were unable to be identified [83], therefore systematically searching the streets in sample areas, and taking photographs for later reference is a more reliable method. Buffer areas are a useful tool for measuring advertising, particularly around specific sites such as schools, although stating advertising was present “around schools” has different meanings when comparing 100 m to 500 m, or to 2 km. GPS and wearable camera technology can identify how individuals encounter food marketing in the routes they use to travel through their environment. These methods should be replicated globally as a more objective measure of individual exposure to outdoor food marketing, although care must be taken in regard to privacy and ethical considerations.

There was little consistency in the methods used to identify persuasive creative strategies, which is typical in the field of food marketing [23]. The heterogeneity observed could be reduced through adherence to protocols for the monitoring of food marketing such as those developed by WHO [51] and INFORMAS [114]. This would improve comparability of future outdoor food marketing data across countries and time points which would better support policy action in this area. Nutrient profiling models are a useful tool for food categorisation, as opposed to grouping foods as “everyday” and “discretionary” or “core” and “non-core”, however, profiling models differ due to cultural differences in diet [106, 115]. There is a need to balance the data required for country-level policy relevance with international comparability. Watson et al. (2021) [106] propose an amalgamation of the WHO EURO NPM and WHO Western Pacific models.

Exposure to outdoor food marketing

Marketing platforms outdoors remain accessible for the food industry and are relatively unrestricted. This is reflected by the extent of advertised food products (22.1%) and the proportion of those that were unhealthy (63%), which is problematic as discrepancies between the food types frequently promoted and dietary recommendations have been linked to changes in dietary norms and food preferences [111]. Whilst fruits and vegetables should make up 40% of daily intake [116], these products were rarely promoted. These findings are comparable to global data of other marketing formats, for example, a benchmarking study found that on average, 23% of advertisements on TV were for foods or beverages, and other studies have found 60–70% of food advertisements to be unhealthy across social media [117,118,119] and in print [120].

This knowledge adds to the existing evidence reporting the extent of children’s exposure through multiple forms of marketing [2, 13, 121]. Whilst efforts are being made to restrict their advertising exposure through other sources such as TV, for consistency, more must be done to protect children in the outdoor environment.

There is no consensus on clear trends in exposure by SES. In part, contradictory findings within this review, such as targeting of wealthier consumers, may reflect the occurrence of a nutrition transition occurring in low income countries, characterised by increased reliance on processed foods [122] which are more available to those with more disposable income. Further research should attempt to develop clear consensus on the differential exposure to outdoor food marketing by SES in both high- and lower-income countries.

Power of outdoor food marketing

The lack of research into the power of outdoor food marketing is most likely a result of the lack of established definitions and classifications for the powerful characteristics of marketing and in particular, child appeal of marketing [123]. The most frequent persuasive creative strategies identified across the twelve studies documenting power were premium offers, promotional characters, health claims, taste appeals and emotional appeals, similar to those identified in television food marketing [23]. These strategies are particularly salient to children: spokes-characters can be effective in influencing children’s food choice, preference, awareness and attention [124], whilst premium offers (e.g. collectible toys) can influence children’s likeability and anticipated taste of the promoted food [125] and can prompt choice of healthier meals [125, 126]. One study found that children were more likely to choose unhealthy food products if they featured nutrient content claims such as “reduced fat, source of calcium” [127]. In this study participants were exposed to unknown brands, it is anticipated that larger responses would be present in brands recognised by participants. Future research should attempt to determine the success of different strategies in influencing behaviour, particularly as the rise in digital media used outdoors may increase the potential for power through increasing the variation and sophistication of outdoor marketing techniques. Policy in this field is largely focused on advertising directed at children, although it is important for research and policy to reflect that due to persuasive creative strategies used, advertising not wholly directed at children can still appeal to them [83].

Impact of outdoor food marketing

There is evidence that outdoor advertising exposure is related to consumption of SSBs and odds of obesity, Previous reviews on the impact of food marketing on television and digital media have found compelling evidence of a relationship between exposure and food intake [44], attitudes and preferences [24]. However, the small number of studies measuring impacts of outdoor food marketing in this review were correlational and therefore cannot demonstrate causality. This lack of evidence is likely preventing policy progress in this area. It is likely that the lack of studies measuring impact of outdoor food marketing is due to the difficulty in controlling for confounding variables in external settings [128] or replicating this form of marketing in a lab compared to other formats such as television. It is clear that unhealthy food marketing is prevalent outdoors, but our understanding of the resultant impacts is underdeveloped and must be further examined through experimental research.

Experimental research will enable clearer understanding as to whether outdoor food marketing influences behaviour as television and digital marketing do [10, 24, 129]. Understanding the impact of outdoor food marketing on body weight would require longitudinal research, although it is difficult to separate the impact of marketing from secular trends. Additionally, there is increasing recognition that attributing a behavioural outcome to a single marketing communication can be problematic and does not appropriately reflect the cumulative effects of multiple, repeated exposures [7]. Purchase data in response to marketing campaigns could be a useful indicator of marketing impact [130], however gathering sales data from industry is problematic. This could be made possible through changes such as those proposed by the UK national food strategy, and supported by the NGO sector [131], calling for mandatory annual reporting of product sales for large food companies [132]. Although this is only proposed in the UK, if the strategy is successful in encouraging companies to make changes to formulations or the proportion of healthy products available, this strategy may be adopted elsewhere.

Strengths

The review was pre-registered, allowing for transparency in approach and reporting of results and the methodology and reporting of the review were robust and consistent with guidelines from both the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews and the JBI methodology. The systematic search strategy ensured a wide range of databases were searched and the identification of a large number of potentially relevant studies. The use of multiple independent reviewers in the full-text screening and data extraction ensured all relevant data was captured accurately.

Limitations

As this is a scoping review, non-peer reviewed sources such as letters to editors [96], conference abstracts [99] and grey literature [104] were included if they met inclusion criteria. Government websites beyond the UK were not included, which is a limitation of our searches, however multiple grey literature sources that were not UK based would have captured relevant international materials. The majority of studies included are focused on advertising and while some marketing aspects are considered, this review does not encompass all marketing communications. However, our searches were designed with thesaurus terms to capture words related to marketing that might not have been realised from a public health perspective. Therefore, it is likely that the relevant literature from marketing disciplines was identified, and is just limited.

As quality assessment was not deemed appropriate, there is potential for error and bias within the included studies, similarly, inaccuracies may arise from the self-reported data used in four studies. Although there were no limitations by language, no translation was required and all eligible studies were published in English. Further, discrepancies in the conduct and reporting of studies make it difficult to collate data and draw firm conclusions.

Conclusions

This review has documented the research on outdoor food marketing exposure, power, and impact. There is substantial heterogeneity in the criteria used to define and methods used to measure outdoor food marketing. Future research will benefit from using a consistent definition and measurement tools to allow for improved comparability between studies. Whilst all the studies documented exposure, few recorded the powerful strategies used in outdoor food marketing and it is still largely unknown how this marketing influences behaviour and ultimately health. In order to inform policy, further research will benefit from examining the causal processes through which outdoor marketing may influence behaviour and health outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the OSF repository, https://osf.io/b65jy/.

Abbreviations

- AMA:

-

American Marketing Association

- GPS:

-

Global Positioning System

- HFSS:

-

High in fats, salt and sugar

- INFORMAS:

-

International Network for Food and Obesity/Non-communicable Diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support.

- NPM:

-

Nutrient Profiling Model

- PROGRESS:

-

Place, race/ethnicity/culture/language, occupation, gender/sex, religion, education, socioeconomic status, social capital

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SSBs:

-

Sugar-sweetened beverages

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Kraak VI, Rincón-Gallardo Patiño S, Sacks G. An accountability evaluation for the International Food & Beverage Alliance’s global policy on marketing communications to children to reduce obesity: a narrative review to inform policy. Obes Rev. 2019;20:90–106.

Backholer K, Gupta A, Zorbas C, Bennett R, Huse O, Chung A, et al. Differential exposure to, and potential impact of, unhealthy advertising to children by socio-economic and ethnic groups: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev. 2021;22(3):e13144.

Loring B, Robertson A. Obesity and inequities: guidance for addressing inequities in overweight and obesity. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2014.

American Marketing Association. 2017. Definitions of Marketing. Available from https://www.ama.org/the-definition-of-marketing-what-is-marketing/

American Marketing Association. n.d. Advertising. Available from https://marketing-dictionary.org/a/advertising/

World Health Organization. Set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Kelly B, King M, Lesley CM, Kathy BE, Bauman AE, Baur LA. A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):e86–95.

Cairns G, Angus K, Hastings G, Caraher M. Systematic reviews of the evidence on the nature, extent and effects of food marketing to children. A retrospective summary. Appetite. 2013;62:209–15.

Ng SH, Kelly B, Se CH, Sahathevan S, Chinna K, Ismail MN, et al. Reading the mind of children in response to food advertising: a cross-sectional study of Malaysian schoolchildren’s attitudes towards food and beverages advertising on television. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–14.

Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with children's fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9(3):221–33.

Boyland EJ, Nolan S, Kelly B, Tudur-Smith C, Jones A, Halford JC, et al. Advertising as a cue to consume: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and nonalcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):519–33.

Goris JM, Petersen S, Stamatakis E, Veerman JL. Television food advertising and the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity: a multicountry comparison. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(7):1003–12.

Calvert SL. Children as consumers: advertising and marketing. Futur Child. 2008;18(1):205–34.

Garretson JA, Niedrich RW. Spokes-characters: creating character trust and positive brand attitudes. J Advert. 2004;33(2):25–36.

Furnham A, Gunter B. Children as consumers: a psychological analysis of the young people’s market. 1st ed. New York: Routledge; 1998.

Harris JL, Fleming-Milici F. Food marketing to adolescents and young adults: skeptical but still under the influence. In: The Psychology of Food Marketing and (Over) eating: Routledge; 2019. p. 25–43.

Harris JL, Brownell KD, Bargh JA. The food marketing defense model: integrating psychological research to protect youth and inform public policy. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2009;3(1):211.

Vukmirovic M. The effects of food advertising on food-related behaviours and perceptions in adults: a review. Food Res Int. 2015;75:13–9.

Taillie LS, Bercholz M, Popkin B, Reyes M, Colchero MA, Corvalán C. Changes in food purchases after the Chilean policies on food labelling, marketing, and sales in schools: a before and after study. Lancet Planet Health. 2021;5(8):e526–e33.

Boyland E, Garde A, Jewell J, Tatlow-Golden M. Evaluating implementation of the WHO set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2018.

Taillie LS, Busey E, Stoltze FM, Dillman Carpentier FR. Governmental policies to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children. Nutr Rev. 2019;77(11):787–816.

Sustain FA. Taking down junk food ads. UK: Susatin; 2019.

Jenkin G, Madhvani N, Signal L, Bowers S. A systematic review of persuasive marketing techniques to promote food to children on television. Obes Rev. 2014;15(4):281–93.

Smith R, Kelly B, Yeatman H, Boyland E. Food marketing influences children’s attitudes, preferences and consumption: a systematic critical review. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):875.

Kelly B, Vandevijvere S, Ng S, Adams J, Allemandi L, Bahena-Espina L, et al. Global benchmarking of children’s exposure to television advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages across 22 countries. Obes Rev. 2019;20:116–28.

Folkvord F, van‘t Riet J. The persuasive effect of advergames promoting unhealthy foods among children: a meta-analysis. Appetite. 2018;129:245–51.

Chow CY, Riantiningtyas RR, Kanstrup MB, Papavasileiou M, Liem GD, Olsen A. Can games change children’s eating behaviour? A review of gamification and serious games. Food Qual Prefer. 2020;80:103823.

Carter M-A, Edwards R, Signal L, Hoek J. Availability and marketing of food and beverages to children through sports settings: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15(8):1373–9.

Bragg MA, Roberto CA, Harris JL, Brownell KD, Elbel B. Marketing food and beverages to youth through sports. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(1):5–13.

Elliott C, Truman E. The power of packaging: a scoping review and assessment of child-targeted food packaging. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):958.

Chu R, Tang T, Hetherington MM. The impact of food packaging on measured food intake: a systematic review of experimental, field and naturalistic studies. Appetite. 2021;105579:1–12.

Prowse R. Food marketing to children in Canada: a settings-based scoping review on exposure, power and impact. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2017;37(9):274.

Chung A, Zorbas C, Riesenberg D, Sartori A, Kennington K, Ananthapavan J, et al. Policies to restrict unhealthy food and beverage advertising in outdoor spaces and on publicly owned assets: a scoping review of the literature. Obes Rev 2021;23(2):e13386.

Roux T. Tracking a lion in the jungle: trends and challenges in outdoor advertising audience measurement. Readings Book. 2017:834–41.

Taillie LS, Reyes M, Colchero MA, Popkin B, Corvalán C. An evaluation of Chile’s law of food labeling and advertising on sugar-sweetened beverage purchases from 2015 to 2017: a before-and-after study. Plos Med. 2020;17(2):e1003015.

Department for Digital Culture Media and Sport, Department of Health and Social Care. Adjusting for displacement London: UK GOV.uk; 2021.

Nott G. How brands can navigate the junk food advertising ban: UK: The Grocer; 2021.

Out of Home Advertising Association of America. History of OOH USA: OAAA; n.d. Available from: https://oaaa.org/AboutOOH/OOHBasics/HistoryofOOH.aspx.

Hastings G, Stead M, McDermott L, Forsyth A, MacKintosh AM, Rayner M, et al. Review of research on the effects of food promotion to children. London: Food Standards Agency; 2003.

Outsmart. Food [Internet]. n.d. [cited 2021, July 05]. Available from https://www.outsmart.org.uk/resources/food

Roux A, Van der Waldt D. Out-of-home advertising media: theoretical and industry perspectives. Communitas. 2014;19:95–115.

Roux AT. Practitioners’ view of the role of OOH advertising media in IMC campaigns. Management. 2016;21(2):181–205.

Boyland EJ, Whalen R. Food advertising to children and its effects on diet: review of recent prevalence and impact data. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(5):331–7.

Russell SJ, Croker H, Viner RM. The effect of screen advertising on children’s dietary intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2019;20(4):554–68.

Cairns G, Angus K, Hastings G. The extent, nature and effects of food promotion to children: a review of the evidence to December 2008: UK: World Health Organization; 2009.

Scully M, Wakefield M, Niven P, Chapman K, Crawford D, Pratt IS, et al. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents’ food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite. 2012;58(1):1–5.

Norman J, Kelly B, Boyland E, McMahon A-T. The impact of marketing and advertising on food behaviours: evaluating the evidence for a causal relationship. Curr Nutr Reports. 2016;5(3):139–49.

Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–7.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. Chapter 11: scoping reviews, Joanna Briggs institute reviewer manual. In: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Boyland E, Tatlow-Golden M, Coates A. Monitoring of marketing of unhealthy products to children and adolescents - protocols and templates: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/activities/monitoring-of-marketing-of-unhealthy-products-to-children-and-adolescents-protocols-and-templates. Cited 2021 June 30.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Lesser LI, Zimmerman FJ, Cohen DA. Outdoor advertising, obesity, and soda consumption: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–7.

Bragg MA, Pageot YK, Hernández-Villarreal O, Kaplan SA, Kwon SC. Content analysis of targeted food and beverage advertisements in a Chinese-American neighbourhood. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(12):2208–14.

Herrera AL, Pasch K. Targeting Hispanic adolescents with outdoor food & beverage advertising around schools. Ethn Health. 2018;23(6):691–702.

Isgor Z, Powell L, Rimkus L, Chaloupka F. Associations between retail food store exterior advertisements and community demographic and socioeconomic composition. Health Place. 2016;39:43–50.

Ohri-Vachaspati P, Isgor Z, Rimkus L, Powell LM, Barker DC, Chaloupka FJ. Child-directed marketing inside and on the exterior of fast food restaurants. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1):22–30.

Adjoian T, Dannefer R, Farley SM. Density of outdoor advertising of consumable products in NYC by neighborhood poverty level. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Barnes TL, Pelletier JE, Erickson DJ, Caspi CE, Harnack LJ, Laska MN. Peer Reviewed: Healthfulness of Foods Advertised in Small and Nontraditional Urban Stores in Minneapolis–St. Paul, Minnesota, 2014. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:1–11.

Basch C, LeBlanc M, Ethan D, Basch C. Sugar sweetened beverages on emerging outdoor advertising in new York City. Public Health. 2019;167:38–40.

Cassady DL, Liaw K, Miller LMS. Disparities in obesity-related outdoor advertising by neighborhood income and race. J Urban Health. 2015;92(5):835–42.

Dowling EA, Roberts C, Adjoian T, Farley SM, Dannefer R. Disparities in sugary drink advertising on new York City streets. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(3):e87–95.

Lowery BC, Sloane DC. The prevalence of harmful content on outdoor advertising in Los Angeles: land use, community characteristics, and the spatial inequality of a public health nuisance. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):658–64.

Lucan SC, Maroko AR, Sanon OC, Schechter CB. Unhealthful food-and-beverage advertising in subway stations: targeted marketing, vulnerable groups, dietary intake, and poor health. J Urban Health. 2017;94(2):220.

Pasch KE, Poulos NS. Outdoor food and beverage advertising: a saturated environment. In: Advances in Communication Research to Reduce Childhood Obesity: US:Springer; 2013. p. 303–15.

Poulos NS, Pasch KE. The outdoor MEDIA DOT: the development and inter-rater reliability of a tool designed to measure food and beverage outlets and outdoor advertising. Health Place. 2015;34:135–42.

Yancey AK, Cole BL, Brown R, Williams JD, Hillier A, Kline RS, et al. A cross-sectional prevalence study of ethnically targeted and general audience outdoor obesity-related advertising. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):155–84.

Zenk SN, Li Y, Leider J, Pipito AA, Powell LM. No long-term store marketing changes following sugar-sweetened beverage tax implementation: Oakland, California. Health Place. 2021;68:102512.

The World Bank. World bank country and lending groups. 2021.

Fernandez MMY, Februhartanty J, Bardosono S. The association between food marketing exposure and caregivers food selection at home for pre school children in Jakarta. Malays J Nutr. 2019;25:63–73.

Yau A, Adams J, Boyland EJ, Burgoine T, Cornelsen L, De Vocht F, et al. Sociodemographic differences in self-reported exposure to high fat, salt and sugar food and drink advertising: a cross-sectional analysis of 2019 UK panel data. BMJ Open. 2021;11(4):e048139.

Amanzadeh B, Sokal-Gutierrez K, Barker JC. An interpretive study of food, snack and beverage advertisements in rural and urban El Salvador. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):1–11.

Bragg MA, Hardoby T, Pandit NG, Raji YR, Ogedegbe G. A content analysis of outdoor non-alcoholic beverage advertisements in Ghana. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e012313.

Busse P. Analysis of advertising in the multimedia environment of children and adolescents in Peru. J Child Media. 2018;12(4):432–47.

Dia OEW, Løvhaug AL, Rukundo PM, Torheim LE. Mapping of outdoor food and beverage advertising around primary and secondary schools in Kampala city, Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–12.

Nelson MR, Ahn RJ, Ferguson GM, Anderson A. Consumer exposure to food and beverage advertising out of home: an exploratory case study in Jamaica. Int J Consum Stud. 2020;44(3):272–84.

Sousa S, Gelormini M, Damasceno A, Moreira P, Lunet N, Padrão P. Billboard food advertising in Maputo, Mozambique: a sign of nutrition transition. J Public Health. 2020;42(2):105–06.

Vandevijvere S, Molloy J, de Medeiros NH, Swinburn B. Unhealthy food marketing around New Zealand schools: a national study. Int J Public Health. 2018;63(9):1099–107.

Velazquez CE, Daepp MI, Black JL. Assessing exposure to food and beverage advertisements surrounding schools in Vancouver, BC. Health Place. 2019;58:102066.

Adams J, Ganiti E, White M. Socio-economic differences in outdoor food advertising in a city in Northern England. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(6):945–50.

Barquera S, Hernández-Barrera L, Rothenberg SJ, Cifuentes E. The obesogenic environment around elementary schools: food and beverage marketing to children in two Mexican cities. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–9.

Chacon V, Letona P, Villamor E, Barnoya J. Snack food advertising in stores around public schools in Guatemala. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(3):291–8.

Egli V, Zinn C, Mackay L, Donnellan N, Villanueva K, Mavoa S, et al. Viewing obesogenic advertising in children’s neighbourhoods using Google street view. Geogr Res. 2019;57(1):84–97.

Fagerberg P, Langlet B, Oravsky A, Sandborg J, Löf M, Ioakimidis I. Ultra-processed food advertisements dominate the food advertising landscape in two Stockholm areas with low vs high socioeconomic status. Is it time for regulatory action? BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–10.

Feeley AB, Ndeye Coly A, Sy Gueye NY, Diop EI, Pries AM, Champeny M, et al. Promotion and consumption of commercially produced foods among children: situation analysis in an urban setting in Senegal. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(S2):64–76.

Huang D, Brien A, Omari L, Culpin A, Smith M, Egli V. Bus stops near schools advertising junk food and sugary drinks. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1192.

Kelly B, Cretikos M, Rogers K, King L. The commercial food landscape: outdoor food advertising around primary schools in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(6):522–8.

Kelly B, King L, Jamiyan B, Chimedtseren N, Bold B, Medina VM, et al. Density of outdoor food and beverage advertising around schools in Ulaanbaatar (Mongolia) and Manila (the Philippines) and implications for policy. Crit Public Health. 2015;25(3):280–90.

Liu W, Barr M, Pearson AL, Chambers T, Pfeiffer KA, Smith M, et al. Space-time analysis of unhealthy food advertising: New Zealand children’s exposure and health policy options. Health Promot Int. 2020;35(4):812–20.

Lo SKH, Louie JCY. Food and beverage advertising in Hong Kong mass transit railway stations. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(14):2563–70.

Maher A, Wilson N, Signal L. Advertising and availability of ‘obesogenic’foods around New Zealand secondary schools: a pilot study. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1218):1–11.

Moodley G, Christofides N, Norris SA, Achia T, Hofman KJ. Obesogenic environments: access to and advertising of sugar-sweetened beverages in Soweto, South Africa, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:1–3.

Olsen JR, Patterson C, Caryl FM, Robertson T, Mooney SJ, Rundle AG, et al. Exposure to unhealthy product advertising: spatial proximity analysis to schools and socio-economic inequalities in daily exposure measured using Scottish Children’s individual-level GPS data. Health Place. 2021;68:102535.

Palmer G, Green M, Boyland E, Vasconcelos YSR, Savani R, Singleton A. A deep learning approach to identify unhealthy advertisements in street view images. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–12.

Parnell A, Edmunds M, Pierce H, Stoneham MJ. The volume and type of unhealthy bus shelter advertising around schools in Perth, Western Australia: results from an explorative study. Health Promot J Austr. 2019;30(1):88–93.

Pinto M, Lunet N, Williams L, Barros H. Billboard advertising of food and beverages is frequent in Maputo, Mozambique. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28(3):365–6.

Puspikawati SI, Dewi DMSK, Astutik E, Kusuma D, Melaniani S, Sebayang SK. Density of outdoor food and beverage advertising around gathering place for children and adolescent in East Java, Indonesia. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(5):1066–78.

Richmond K, Watson W, Hughes C, Kelly B. Children’s trips to school dominated by unhealthy food advertising in Sydney, Australia; 2020.

Robertson T, Lambe K, Thornton L, Jepson R. OP57 socioeconomic patterning of food and drink advertising at public transport stops in the city of Edinburgh, UK: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2017.

Sainsbury E, Colagiuri S, Magnusson R. An audit of food and beverage advertising on the Sydney metropolitan train network: regulation and policy implications. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):1–11.

Settle PJ, Cameron AJ, Thornton LE. Socioeconomic differences in outdoor food advertising at public transit stops across Melbourne suburbs. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(5):414–8.

Signal LN, Stanley J, Smith M, Barr M, Chambers TJ, Zhou J, et al. Children’s everyday exposure to food marketing: an objective analysis using wearable cameras. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2017;14(1):1–11.

Timmermans J, Dijkstra C, Kamphuis C, Huitink M, Van der Zee E, Poelman M. ‘Obesogenic’School food environments? An urban case study in the Netherlands. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):619.

Trapp G, Hooper P, Thornton L, Mandzufas J, Billingham W. Audit of outdoor food advertising near Perth schools: building a local evidence base for change Western Australia; n.d. [Cited 2021, June 30].

Walton M, Pearce J, Day P. Examining the interaction between food outlets and outdoor food advertisements with primary school food environments. Health Place. 2009;15(3):841–8.

Watson WL, Khor PY, Hughes C. Defining unhealthy food for regulating marketing to children—what are Australia’s options? Nutr Diet. 2021;78:406–14.

Statista Research Department. Share of digital in total out-of-home (OOH) advertising revenue in the United Kingdom (UK) from 2011 to 2020 UK: Outsmart Out of Home; 2021. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/535387/digital-outdoor-advertising-revenue-in-the-uk/. Cited 2021 June 30.

Tatlow-Golden M, Boyland E, Jewell J, Zalnieriute M, Handsley E, Breda J, et al. Tackling food marketing to children in a digital world: trans-disciplinary perspectives. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2016.

Vogel C, Zwolinsky S, Griffiths C, Hobbs M, Henderson E, Wilkins E. A Delphi study to build consensus on the definition and use of big data in obesity research. Int J Obes. 2019;43(12):2573–86.

Rowe G, Wright G. The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: issues and analysis. Int J Forecast. 1999;15(4):353–75.

Yoo CY. Unconscious processing of web advertising: effects on implicit memory, attitude toward the brand, and consideration set. J Interact Mark. 2008;22(2):2–18.

Larson MR. Social desirability and self-reported weight and height. Int J Obes. 2000;24(5):663–5.

Rzotkiewicz A, Pearson AL, Dougherty BV, Shortridge A, Wilson N. Systematic review of the use of Google street view in health research: major themes, strengths, weaknesses and possibilities for future research. Health Place. 2018;52:240–6.

Mackay S, Molloy J, Vandevijvere S. INFORMAS protocol: outdoor advertising (school zones). New Zealand: University of Auckland; 2017.

Wicks M, Wright H, Wentzel-Viljoen E. Assessing the construct validity of nutrient profiling models for restricting the marketing of foods to children in South Africa. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74(7):1065–72.

Public Health England. In: England PH, editor. The Eatwell guide: how to use in promotional material. UK: Gov.UK; 2018.

Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Roy EA, de Billy N, Czoli C. Children and adolescents’ exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14(6):e12508.

Holmberg C, Chaplin JE, Hillman T, Berg C. Adolescents’ presentation of food in social media: an explorative study. Appetite. 2016;99:121–9.

Qutteina Y, Hallez L, Mennes N, De Backer C, Smits T. What do adolescents see on social media? A diary study of food marketing images on social media. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2637.

Kelly B, Chapman K. Food references and marketing to children in Australian magazines: a content analysis. Health Promot Int. 2007;22(4):284–91.

Boyland E, Tatlow-Golden M. Exposure, power and impact of food marketing on children: evidence supports strong restrictions. Eur J Risk Regul. 2017;8(2):224–36.

Popkin BM, Adair LS, Ng SW. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(1):3–21.

Mulligan C, Potvin Kent M, Vergeer L, Christoforou AK, L’Abbé MR. Quantifying child-appeal: the development and mixed-methods validation of a methodology for evaluating child-appealing marketing on product packaging. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9):4769.

Elliott C, Truman E. Measuring the power of food marketing to children: a review of recent literature. Curr Nutr Rep. 2019;8(4):323–32.

McAlister AR, Cornwell TB. Collectible toys as marketing tools: understanding preschool children’s responses to foods paired with premiums. J Public Policy Market. 2012;31(2):195–205.

Hobin EP, Hammond DG, Daniel S, Hanning RM, Manske SR. The happy meal® effect: the impact of toy premiums on healthy eating among children in Ontario, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(4):e244–e8.

Dixon H, Scully M, Niven P, Kelly B, Chapman K, Donovan R, et al. Effects of nutrient content claims, sports celebrity endorsements and premium offers on pre-adolescent children’s food preferences: experimental research. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9(2):e47–57.

Wilson RT, Baack DW, Till BD. Creativity, attention and the memory for brands: an outdoor advertising field study. Int J Advert. 2015;34(2):232–61.

Kelly B, Vandevijvere S, Freeman B, Jenkin G. New media but same old tricks: food marketing to children in the digital age. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(1):37–45.

Kovic Y, Noel JK, Ungemack J, Burleson J. The impact of junk food marketing regulations on food sales: an ecological study. Obes Rev. 2018;19(6):761–9.

Obesity Health Alliance. Turning the tide: a 10-year healthy weight strategy. UK: Obesity Health Alliance; 2021.

Dimbleby H. National Food Strategy: the plan. UK: National Food Strategy; 2021.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The first author (AF) is funded by an ESRC case studentship, grant no: ES/P000665/1, with a contribution from the Obesity Health Alliance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EB and ER were involved in the conception of the study. The review protocol, design and extraction instrument were developed by AF, EB, ER, AJ and M.Ma. The search strategy was developed by AF and M.Ma. Searches, title and abstract screening and full text screening were completed by AF. A second independent full text screening of articles was completed by RE, HM and M.Mu. Data extraction was completed by AF, RE, HM and M.Mu. The manuscript was written by AF and EB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ER has previously received research funding from Unilever and the American Beverage Association for unrelated research projects. All other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Finlay, A., Robinson, E., Jones, A. et al. A scoping review of outdoor food marketing: exposure, power and impacts on eating behaviour and health. BMC Public Health 22, 1431 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13784-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13784-8